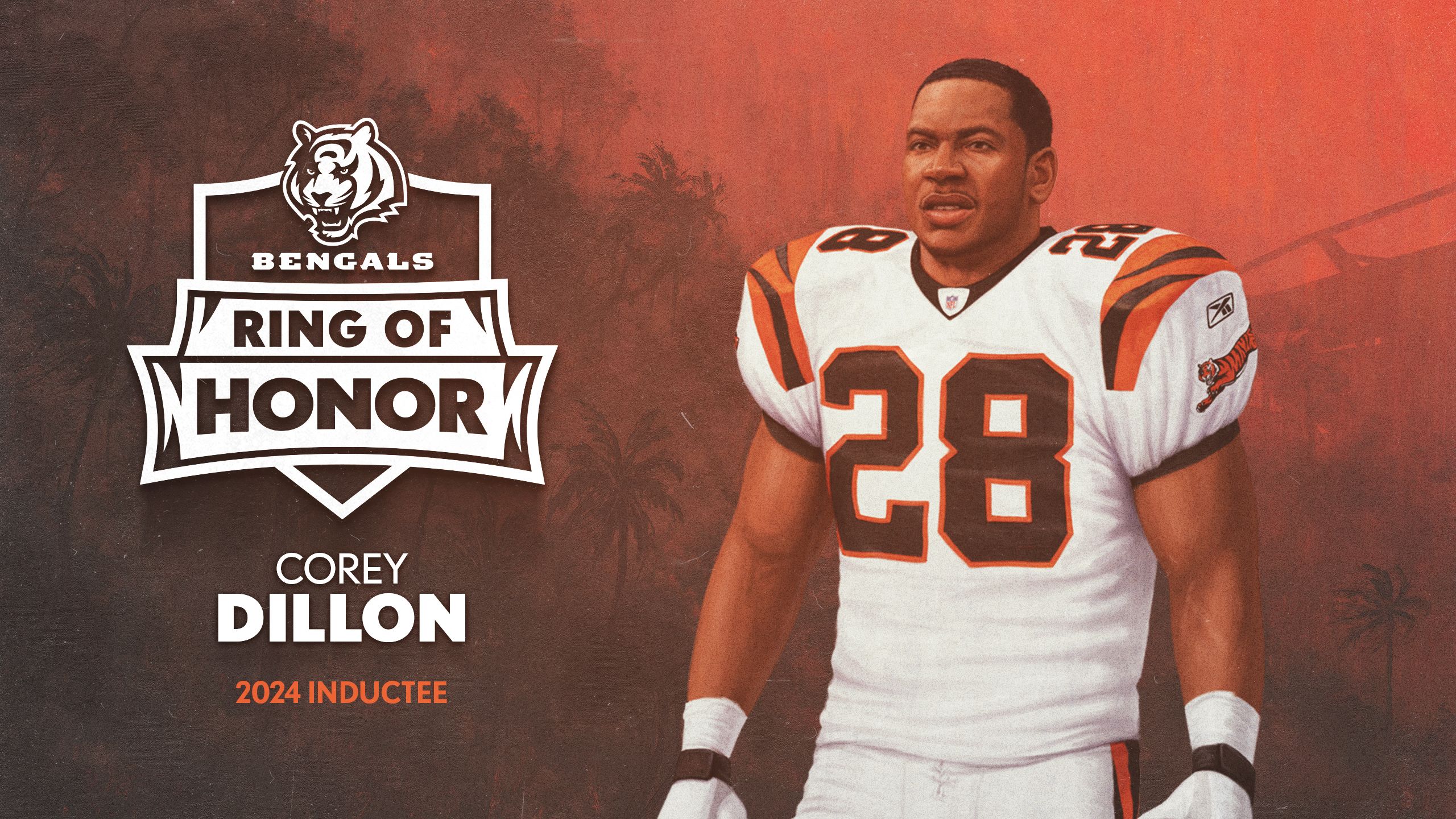

This time, a generation after the Bengals sifted their greatest running back out of the 1997 NFL Draft's second round, Corey Dillon took the call.

This time it was Bengals president Mike Brown, who took Dillon's card off the wall 27 years ago, making the call to tell him the club's season ticket-holders had voted him into the Ring of Honor.

"It was a beautiful conversation, man. To be honest with you, it was just like appreciating each other. I deeply appreciated that call from him," says Dillon, recalling how he was on the brink of tears. "That meant a lot to me to finally have that conversation. It felt like we put a lot of stuff to rest just with that conversation alone.

"He said, 'We're putting you in this year', and it meant a lot for me to hear these words. 'You deserve to be in there,' and I was like, 'I appreciate it. I deeply appreciate it.' And I just told him thanks for drafting me and allowing me to grow. And he thanked me for everything I did for the organization. It was just a good conversation."

Dillon has to laugh about missing that first call all those years ago. After the Packers took Iowa tackle Ross Verba with the last pick of the first round, Dillon shot out of his home at 23rd Avenue on the street known as "The Blade," that cut through Seattle's rough-and-tumble Central District.

Furious he was still on the board, Dillon left behind a house where everyone "was having a jolly good time." It only took 13 more picks. His brothers had to go find him when the Bengals took him right after the Cardinals drafted Arizona State quarterback Jake Plummer at No. 42.

He was talking to no one. They found him outside "chilling," but he was really smoking with another log tossed on one of the most competitive fires Cincinnati has ever seen. After a star-crossed youth and stints at two junior colleges before tearing up his lone year back home at the University of Washington, Dillon raged with the knowledge he had to prove himself all over again.

"That set me up. I had no choice," Dillon says. "I had purpose of making a name for myself. That was number one. The whole draft scenario pissed me off, but it just put another chip on my shoulder. 'Okay, so that's what you think.' I was even more inspired to go out there and prove myself."

The 6-1, 225-pound Dillon came in running angry and he never stopped. While doling out the NFL's most lethal turn-of-the-century stiff arm, he became the Bengals' all-time leading rusher with 1,000 yards in his first six seasons taking the ball from eight starting quarterbacks.

The fire-and-brimstone supplied infernos for two of the NFL's 13 biggest rushing games while melting long-standing records set by Hall-of-Famers.

He zapped Jim Brown's 40-year-old rookie rushing record with 246 yards in his fourth NFL start and then chased down the late Walter Payton's 23-year-old all-time record with those 278 yards on a mere but iconic 22 carries that gave the Bengals their first Paycor Stadium win in 2000.

"I believe some things are not meant to be touched. You know what I mean?" Dillon says of the Payton game. "And that was one of them and I'm blessed to actually surpass that. That was kind of overwhelming."

Dillon is the first to tell you he was pretty much untouchable during his run here and if he has any regrets it's that his personality was so hot to the touch that he didn't let anybody get close and that led to some crossed signals.

He doesn't run so hot now. "I've got some anti-freeze. I'm as cool as the other side of the pillow." He says Corey Dillon at 49 years old is a different man than the kid who turned 26 the week he ran down Payton. Back then, he says, the fire engulfed him.

But he's had so much time to think since his career ended that he immediately realized the significance of the date of the Ring of Honor game at Paycor against Washington.

Sept. 23.

Two years to the day his mother died. Jerline Dillon clipped every word written about her youngest. He used to shake his head when he saw the scrapbooks because she also worked full-time. "Where do you have the time?"

Now he knows all about time.

"I had an awakening two years ago when my mom passed. Because we're not guaranteed tomorrow," Dillon says. "The majority of my life has been football and I've just been caught in that moment. Of trying to be the best version of a football player and make a name for myself and chasing down a damn championship. Sometimes that stuff can consume you."

He recently moved down the California coast to a home in Anaheim Hills, where he says he'll walk out back, puff a cigar, "and gaze for hours." It's a manicured metaphor because he says he's in a much better place than even just a few years ago. The one-time quintessential homebody enjoys traveling to Hawaii and has London in his sights.

"More low key," Dillon says. "I'm expanding my horizons."

But there's still a ring of fire in this newest ring of honor member. After years of trying to discover the post-football Corey Dillon, he concluded he's not much different than the player Corey Dillon.

"I'm a real good dude, but don't screw with me," he says.

When he vented about not making The Ring last year, this new version of Dillon re-evaluated and listened to die-hard Bengals fans who reached out. He became a podcast regular with Strawberry Ice. He accepted an invite from Bengals Captain to attend the Buffalo game. He knew the fans love him and that he loves them, but to be awash in that love in the pregame end zone crowd drove it home.

"I think me coming back down there and opening up and people getting to see me for who I am, it kind of softened some of the bitterness," Dillon says.

For years he's been telling fans that his last act as a Bengal wasn't one of defiance, but respect. When he tossed his uniform piece by piece into the stands after the 2003 finale, he sensed it was his last game in the stadium and he felt like he was leaving a chunk of him before he left to pursue a Super Bowl he helped Tom Brady win the next season.

"It wasn't a gesture of screw you. Take the uniform," Dillon says. "What better way to pay back the support of the fans and let them have my equipment knowing some would sit on it for years?"

He was vindicated back in 2017 when he returned as one of the First 50 players in franchise history. At an autograph signing, he was suddenly looking down at the helmet he wore that day.

"Mouthpiece intact," Dillon says.

Now No. 28 is coming out of the crowd into The Ring and it's quite fitting he'll be up there with the No. 71 of his good friend and right tackle for all of those yards. Willie Anderson was so good they named their basic run play after him, 16 Willie, and it was Dillon's bread-and-butter on that crazy, nutty day he went for 278 despite 10 carries for a yard or less.

"Nobody has ever had a game like that. What's that? Something like 12 and a half yards a carry on those other runs," Dillon says. "We ran (16 Willie) to death. Just a 34 zone. I'm just doing my zone steps and my aiming point is Willie. And I'm going off if Willie has him inside or outside.

"And once I get there, it's up to me to make that cut and get up field with the ball."

Ring of Honor

The official source of Bengals Ring of Honor nominees, inductees, and more.

It was Dillon's old-school style at its best and the run goes on in an endless text chain that includes Bengals from that day (among them Anderson, Adrian Ross, Peter Warrick) and Bengals who came later, such as Levi Jones, T.J. Houshmandzadeh, Chad Johnson.

"The list goes on," Dillon says. "Those guys are crazy, man. We're in contact. That's what it's

supposed to be about. I understand how things could get misconstrued as we're playing. But as we're retired, we're all mature about where we're at in life and when we look back on it, it wasn't as bad as it seems. There's a lot of good that came from that. We've got good Bengals brothers."

Thursday's announcement of Dillon joining The Ring is going to blow up everyone's phone. And the three girls probably already know.

Dillon's two youngest daughters, Carly, a sophomore at Howard, and Deavan, a high school senior, may have to miss some classes. His oldest, Cameron, 25, works in the fashion industry, and her dad is looking forward to her coming back to her place of birth.

"That's one of the reasons the city means so much to me," Dillon says.

The honor re-opens his case for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. "I check almost every box," he says. And he'll tell you how he's got better numbers than O.J. Simpson ("God rest his soul"), as well as how he and Hall of Fame finalist Fred Taylor compare notes and wonder why they're not in.

(Footnote: Dillon is one of six running backs post-1967 with at least four seasons of 1,100 yards rushing and 4.6 yards a carry. Only Taylor and Hall-of-Famer Barry Sanders have more with seven each.)

But there's no debate on a special Sept. 23 when Dillon takes his place in Bengals history.

"There's a whole lot of stuff to be thankful for," Dillon says. "There's a lot of stuff I would have done differently, but I wouldn't change this moment for the world. This is it. This is what it's supposed to be."